SVA Assessment – China's Anti-Corruption Campaign – Risks to Foreign Business

The anti-corruption campaign in China, now in its third year, shows no signs of slowing. Indeed, the campaign is without precedent in recent Chinese history and presents real risks to foreign businesses, as it is rooting out longstanding patronage networks, altering accepted working practices and dampening sentiment in key markets. This situation poses real risks for foreign investors, both in China and elsewhere, as accusations can prompt mirror investigations under the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (“FCPA”) or the UK Bribery Act, amongst others. Foreign investors in China thus need to mitigate their exposure, or risk steep penalties.

The Anti-Corruption Campaign

Chinese Communist Party (“CCP”) General Secretary Xi Jinping launched the anti-corruption campaign in November 2012; it has since set records. The Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (“CCDI”), the CCP’s internal policing mechanism, claimed in 2014 to have carried out 53,085 investigations, disciplined 71,748 cadres and “severely disciplined” 23,646 – double the numbers in 2013, of 24,521 investigations, 30,420 disciplinary actions, and 7,692 incidences of severe disciplinary action.

The campaign serves several purposes. Perhaps most obviously, it is a political initiative aimed at those opposed to CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping. However, it is not just a purge. Xi seemingly also wants to root out the graft that threatens the CCP’s legitimacy; indeed, his public statements as far back as the 1980s dwell on the threat of corruption. A third motive probably relates to reform. After all, CCDI head Wang Qishan built his reputation by forcing change in the financial sector. Wang may see the anti-corruption campaign as a means to deter vested interests from blocking reform.

Tigers and Flies

The state media has talked of “tigers and flies”, meaning high and low level corrupt officials. The first big tiger to fall was Bo Xilai, former Party Secretary for Chongqing Municipality. Bo’s crimes were largely political – of seeking membership of the Politburo Standing Committee (“PBSC”) through populism; he was thus a threat to Xi Jinping. His downfall came after his lieutenant Wang Lijun sought asylum at the US Consulate in Chengdu in February 2012, asserting that Bo’s wife had murdered a British businessman. A court sentenced Bo to life in prison for graft in September 2013.

The anti-corruption campaign then shifted its focus onto Zhou Yongkang, who chaired the PBSC Politics and Legal Affairs Committee from 2007 to 2012, giving him control over China’s security services. Investigations started low, rising to associates such as Li Dongsheng, Vice-Minister for Public Security, Jiang Jiemin, former General Head of China National Oil Corporation (“CNPC”), and Li Chuncheng, former Deputy Party Secretary of Sichuan. After dismantling his patronage network, the state media announced Zhou’s expulsion from the CCP in December 2014. He now faces trial for graft, and perhaps the death sentence.

A third line of inquiry focused on Ling Jihua, an ally of former CCP General Secretary Hu Jintao. Ling was a strong candidate for promotion to the highest level, until his son and two women died in a Ferrari crash in March 2012, provoking a scandal that led to his sidelining. Starting low again, investigations rose to ensnare his family and associates in Shanxi province. The state media announced a formal investigation in December 2014; Ling now faces expulsion from the CCP, and a trial.

Other tigers have included Su Rong, the former Vice-Chairman of the Central People’s Political Consultative Congress, and General Xu Caihou, a former Vice-Chairman of the Central Military Commission, although these cases are just the most notable. Investigations into the People’s Liberation Army (“PLA”) have also increased rapidly, and the campaign has rounded up thousands of more vexatious “flies”, who arguably present a greater threat to CCP legitimacy.

The Risks to Foreign Business

This campaign is not just a political curiosity – it poses real risks to foreign investors. Companies suffer when they lose political protection. Kaisa Group, a property developer, foundered after the arrest in October 2014 of Jiang Zunyu, former head of Shenzhen’s police, owing to links to Zhou Yongkang’s son. The arrest in turn prompted Kwok Ying Shing, Kaisa’s chairman, to resign in December. The company then missed payment on a USD51 million loan on 5 January, triggering cross-default clauses on loans worth some USD10 billion, much of which appears to be irrecoverable. Kaisa’s finances seemed sound before the arrest; it was politics that provoked the collapse.

Other risks relate to uncertainty, as accusations can sap confidence. The Ling Jihua case in January 2015 spawned inquiries into Founder Group, a technology company linked to Peking University, after property firm Beijing Zenith alleged embezzlement. That claim led to investigations into Ma Jian, a vice-minister at the Ministry of State Security, and then into Minsheng Bank, one of China’s biggest private banks. Suddenly, the financial sector was a prospective target; investigations moved onto Bank of Beijing in early March.

The campaign has also changed the business climate. Pharmaceutical company GlaxoSmithKline (“GSK”) came under investigation for bribery in the spring of 2014; the authorities levied a fine of USD500 million in October 2014, and handed out jail sentences – a three year suspended sentence for Mark Riley, GSK’s former head in China, and a draconian 19 years for a Shanghai health official. The case is important, because GSK’s activities were illegal, but had been typical. More broadly, concerns are rising about weak auditing of state owned enterprise assets, and the campaign has dampened sentiment in certain markets, leading to weaknesses in sectors such as luxury goods and gaming.

How Can Foreign Firms Limit Their Exposure?

Foreign businesses must respond to these risks. A key first step is to identify how exposed any current business partner or corporate executive might be. Patronage networks can stretch far, though, so the risks can be wider than expected. Zhou Yongkang’s support network included former Politburo Standing Committee member Zeng Qinghong and former CCP General Secretary Jiang Zemin, meaning any risk appraisal needs to take account of their ties. One tangential link derived from Jiang’s son, Jiang Mianheng, who has considerable sway over China Unicom, meaning that the mobile telephony sector might face investigations and negative outcomes.

A second key step is to identify upcoming risks. Rumours suggest that the family of former premier Li Peng is exposed, potentially affecting energy companies under their sway. Another risk is emerging in Jiangsu Province, where Yang Weize, the Party Secretary of Nanjing, in January came under investigation, a year after the expulsion of Ji Jianye, the Mayor of Nanjing, from the CCP. These investigations hint at a target in Li Yuanchao, Politburo member and ally of Hu Jintao; Li was Party Secretary of Jiangsu between 2002 and 2007.

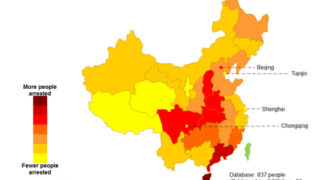

It is possible to asses risk on a geographical and sectoral basis. In terms of geography, the locations most at risk may include Hainan Province, Guangdong Province, Chongqing Municipality, Sichuan Province, Shanxi Province, Jiangxi Province, Shandong Province, Shanghai Municipality and Jiangsu Province.

In addition, a non-exhaustive summary of sectors most at risk might include Gaming (Macau), Energy (oil and gas), Property development, Education, Energy (electricity), Telecommunications, Banking and Finance, Healthcare and Pharmaceuticals, Resources, Luxury Goods.

Positive Aspects of the Campaign – Opportunities Arising

A further requirement for foreign business is to identify who might benefit from the campaign. At first glance, the most obvious beneficiaries are Xi Jinping and CCDI head Wang Qishan. The CCDI is an institutional victor, as its officials now have power to influence decisions throughout government; it has come to resemble the Censorate, a parallel administration in imperial times that reported directly to the emperor on malfeasance. The purge has also opened up space for others’ advancement. 46 new officials have taken roles on the People’s Political Consultative Conferences in 28 provinces in recent months. Officials from Zhejiang, Fujian and the Nanjing Military Region, where Xi built his career, have reportedly also advanced. Another victor may be Anbang Insurance, which has expanded rapidly in recent months – including by taking a major stake in Minsheng Bank. Its backers include Wu Xiaohui, the husband of former core leader Deng Xiaoping’s granddaughter, and Chen Xiaolu, the son of Mao-era general Chen Yi. Any business that can identify winners early could forge links providing a real competitive advantage.

Conclusion

The anti-corruption campaign under way in China is without precedent in scale. It has turned some well-connected individuals into liabilities, altered hitherto accepted working practices, and dampened appetite in certain sectors. This situation poses real risks for foreign investors, both in China and elsewhere, as accusations can prompt mirror and serious investigations under the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (“FCPA”) or the UK Bribery Act, amongst others. Foreign investors in China need to mitigate their exposure or face steep penalties.

SVA are in a position to assist by conducting an independent and comprehensive assessment of major companies’ China-based activities, by identifying potential triggers for investigation, and by advising on how best to mitigate against risk. SVA has considerable experience in guiding corporations and their boards of directors, and in working with corporate counsel, in doing so.

SVA’s experience is that any such exercise must occur separately from local and regional management, and that discreet reporting to the most senior levels of the company concerned is essential. Any such action must also be timely. Action in response to an investigation comes too late to protect the company’s interests in China and, perhaps, its global brand; retaining counsel at this late stage may have only limited benefits, owing to the uncertain legal environment in China.

If you wish to protect your business from the negative consequences of exposure to these risks, SVA can be of assistance. Please do not hesitate to contact us at the numbers below or via e mail to [email protected].